Written by Susan Cummings-Lawrence

The online exhibit “Anshe Sfard, Portland’s Early Chassidic Congregation” written by Susan Cummings-Lawrence can be found on the Maine Memory Network.

Ghosts

There is something compelling for certain people in the stories of absence and loss. I am one of those people, it seems. The why’s and how’s that are more or less easy to figure out¾well, they are too easy. When a building stands and images of its life are accessible, where is the mystery? Sometimes it is the ghosts that are more enticing than the breathing. How did these once living souls and institutions arrive at their eventual ethereal state? What changes took place and how did they come about? What social forces were in play that would cause a community and its institutions to be born and to die and to be reincarnated “at a new address,” as Simon Schama would say?[i] What memories of the past helped to shape the lives of those whose present and future were to be so shockingly new?

In the course of my community history work in Greater Jewish Portland in recent years, I have always been eager to hear stories about everything and everyone. Having grown up here, however, I recalled a synagogue of which, it seemed, no one I met had been a member; no one I met talked about it. The shul that wasn’t there. Except it was there.

My initial explorations turned up a demolition photo. That was it! Eventually I was able to learn more about the founding of this congregation, Bas HaKnesses Anshe Sfard. But primarily what I uncovered, in this case, was how easily and completely even recent memory fails. Instead of a cache of interesting images, I found dismal urban renewal and demolition photos. Anshe Sfard Judaica was scattered here and there and was unrecognizably assimilated into other synagogues’ Judaica, or was hiding in plain sight. Descendants of founding and more recent members also were scattered and memories were few. Architectural drawings had completely disappeared. In fact, much of the neighborhood to which members had immigrated had disappeared, destroyed by poverty, the blight of urban renewal and a lack of will and vision on the part of local government to resist the tide of urban renewal ubiquitous in the 1960s and 1970s. Coupled with apparently little institutional planning and foresight on the part of Anshe Sfard, and with normal assimilation patterns piled on, it was a trifecta. Anshe Sfard was born and died in barely fifty years.

Let’s take a closer look at the memory of this world.

In the beginning

Although not much is commonly known about the United States presence of pre-World War II Chassidic Jews, there were many communities of Chassidim all over the US and Canada.[ii] Portland had such a community, with its own synagogue in the Bayside area of the city.[iii]

Bas HaKnesses Anshe Sfard (House of Assembly of the Men of Spain) members coalesced around traditions slightly different from those of their Orthodox contemporaries. These practices were associated with their homes of origin, in this case primarily Poland. Eastern Europe had been influenced by Jewish diaspora populations, originally from Spain, as they moved into and through Arab countries and beyond. As is typical of many religious practices, it is also likely that certain of these communities sought to differentiate themselves further from other Jews by adopting the Sephardic style of nusach.

The prayer book used by this congregation is the same type that is still used by the Chabad Lubavitch, but it actually contains only a few minor differences distinguishing it from a typical Modern Orthodox siddur. Chabad Lubavitch, was founded in the late 18th century by Shneur Zalman of Liadi and takes its name from Lyubavichi, the Russian town where the group was based until the early 20th century.[iv]

So, what is the connection to Sephardic practice? Chassidism owes much to Kabbalah and to 16th century Jewish mystic, Rabbi Yitzhak ben Shlomo Luria Ashkenazi (Isaac Luria).[v] Although whether Luria is of Sephardic descent is debated, he lived in the land of Israel and in Egypt, and was thus surrounded by Sephardi and Mizrachi Jews. He almost certainly had an entirely Sephardic style of prayer.[vi] Luria is considered the father of contemporary Kabbalah, elemental in Chabad thinking and practice. Because of their mystical background and outlook, some Chassidim follow the liturgical rites taught by classical Kabbalistic rabbis such as Luria. Nusach Ari is a liturgy based on Luria’s custom, and Nusach Sfard is a similar liturgy based on Sephardic custom. For the most part, however, rather than having been descendants of Spanish Jews, both Anshe Sfard members and the Lubavitch community were Eastern European Chassidim, not Sephardim, and use the Nusach Ari.

Early Days

The original Portland group, most of whom either came directly from Poland and Russia or had other Eastern European ancestry, met before the turn of the century in different locations in the India Street area, including Bet HaMidrash HaGadol , known as Abrams’ Shul, on the corner of Hampshire and Fore Streets, and after 1904 when it was built, in the basement of the old Shaarey Tphiloh on Newbury Street. Led by Abraham Seigal, Abraham Isenman and David Finkelman, in 1917 they constructed their own synagogue at 216 Cumberland Avenue. It was designed by the well-known Portland architectural firm of Francis and Edward Fassett.[vii],[viii] Drawings and blueprints have been lost,[ix] but the City of Portland building permit offers the most basic information.

The sixty years of reconstruction following the Portland fire of 1866 and the devastation of the Civil War, and coinciding with European immigration in Portland and WWI, made for an exciting time of change and variety on the Portland peninsula. Architects, builders and investors were busy erecting hundreds of new buildings to replace and improve upon those that were destroyed. According to the Portland Directory, by 1917, there were approximately seventy churches and synagogues in the city, many of them in the Bayside neighborhood where Anshe Sfard was built.[x] Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, and Armenian groups, as well as Jews, were busy creating communities in Bayside that were self-sustaining, and in many cases included their own places of worship, business and communal gathering. Others, such as the Chinese and the Irish, maintained businesses and attended churches and schools in Bayside.

Maine Jews were predominantly Orthodox during this dynamic period of growth, immigration and early assimilation. Many, though, had other thoughts and plans even while attending an Orthodox synagogue. The year that Anshe Sfard was built, the Modern Synagogue Society, led by Elias Caplan and a few other men, worked with the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary of New York and obtained the services of a rabbi. They called themselves Temple Israel and met at the Young Men’s Hebrew Association hall on Wilmot Street. But internal conflicts and outside pressures from the Orthodox were too powerful to overcome and the group’s efforts subsided in 1919. Many of them met afterward at the synagogue that became Etz Chaim. They remained relatively quiescent until the 1940s when Conservatives gained strength and numbers and were thus able to make the transition from marginality to provisional acceptance.[xi]

Even before 1920, the assimilation process was well underway. The nation-wide Americanization movement, which was intended to mollify citizens feeling threatened by foreigners and to boost immigrant assimilation, began in post-war 1922 and continued through 1945. In Portland it manifested itself through classes offered at nearby North School at the foot of Munjoy Hill and at the Woolston School on Chestnut Street in Bayside attended by many Jewish immigrants.[xii] Many Jewish businesses and mission-driven organizations for both men and women were being established at this time. Synagogues, including Anshe Sfard, developed their own sisterhood groups and various chevrei kadisha, but the community-based groups drew membership from the local Jewish population.

From the turn of the century, there were both a Young Men’s Hebrew Association and a Young Women’s Hebrew Association. Undoubtedly, men and women from Anshe Sfard were involved in these associations. They met on Wilmot Street around the corner from the shul until the late 1930s when the Jewish Community Center was established on nearby Cumberland Avenue. The YMHA then became the Center Women’s Group. Although the first board of directors was composed of just one woman and several men, it was these women who were responsible for the development and founding of the Jewish Home for the Aged, now The Cedars.[xiii]

In general, membership in non-Jewish civic groups came later, but the groundwork was being laid for the nearly full integration of the 1960s.

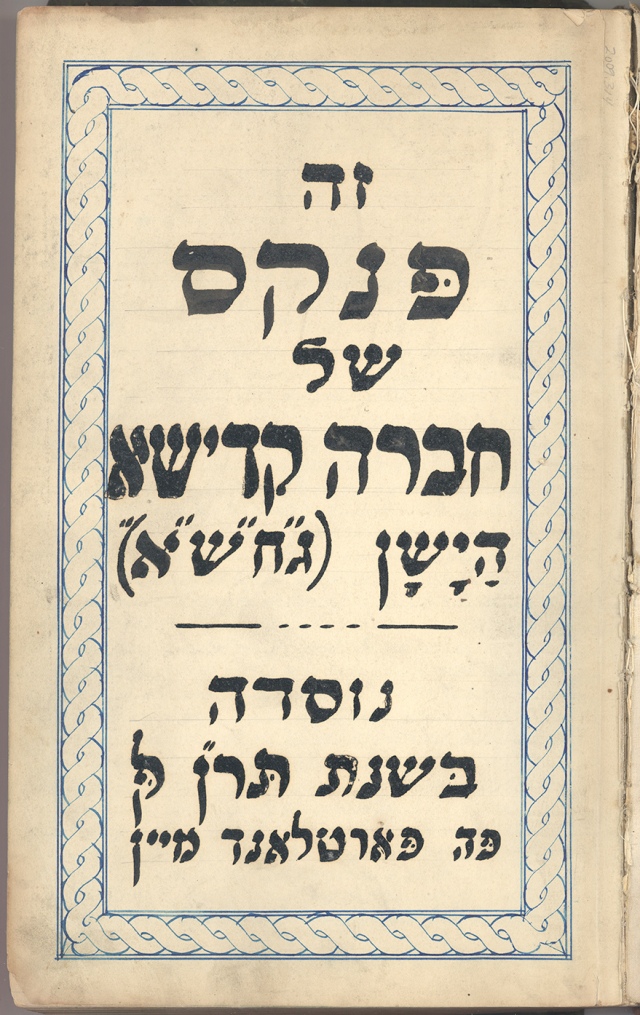

Portland Orthodox communities worked hard, as others did nationally, to negotiate the territory between traditional religious practice and adaptation to new societal demands and influences.[xiv] They were people “…struggling to remain who they are while becoming someone else.”[xv] In spite of the energy required to achieve and maintain this balance, both Orthodox and Conservative groups continued to expand, reaching high levels of institutional affiliation and activity through the 1970s. Anshe Sfard continued to grow from the 1920s through the 1940s, and established itself as an active congregation striving to meet the needs of its members. In 1924, the membership of Anshe Sfard purchased property on Hicks Street in Portland for its own cemetery. Thirty-five years earlier, in 1889, a group of men had formed a burial society, later referred to as the Alte (Old) Chevra Kadisha. (When another Chevra Kadisha developed in 1916, it was called the New Chevra Kadisha.) It was supervised by Isaac Santosky and was associated with those who later formed the larger group that was to become Anshe Sfard. [xvi]

When it was founded, this chevra kadisha of the founding Chassidic families had purchased a small plot in the same Hicks Street location; it was later incorporated into the larger cemetery. Mt. Carmel Cemetery, adjacent to Mt. Sinai Cemetery founded in 1894, shares part of its eastern boundary. It currently has over 350 burials, the latest in 2013.[xvii] Longtime trustees, cousins Gerald and Arthur Cope, still maintain oversight.

Hard Times

Anshe Sfard’s arc was brief. The synagogue, erected in 1917, was closed for good in only fifty years. In the 1940s and 1950s, the thriving Jewish communities of Bayside, Munjoy Hill and India Street began to disperse, making their way off the urban peninsula to the Woodfords area. Temple Beth El, a Conservative congregation a long time in the making, formed in 1947, met briefly at 509 Forest Avenue before moving into its forward-looking modern building at 500 Deering Avenue in 1950. As Carol Herselle Krinsky points out, assimilation in general culture and assimilation in architecture often go together.[xviii] Recognizing the need to keep up with his own members’ move to the suburbs, which signaled a change in social status, Rabbi Bekritsky of Shaarey Tphiloh urged the construction of a new building on Noyes Street in 1954—another “modern” building.[xix] The designs of both Temple Beth El and Shaarey Tphiloh were a giant step into the future and away from the typical European style they had shared with Anshe Sfard.

Furthermore, Rabbi Bekritsky’s response to Conservative Judaism in the community was swift and sharp. Orthodoxy was far more threatened by Conservative Judaism than by Reform Judaism because they were very similar. Reform Jews were not regarded as real Jews, whereas Conservatives were seen to be in need of merely a course correction; they had to be redirected to the correct path from which they had slightly, but dangerously, strayed. Bekritsky was dedicated to thwarting the creation of this community and no doubt hoped that proximity to Beth El would have a salutary effect.[xx] The Jewish Community Center stayed at the old Pythian Temple building at 341 Cumberland Avenue, acquired in 1938, until 1985 when it also moved to the same neighborhood, 57 Ashmont Street in Woodfords. The Portland Jewish Funeral Home had moved from 15-17 Locust Street to 471 Deering Avenue in 1974.

Anshe Sfard remained for several more years at its spot where Franklin Street, Quincy Street, Wilmot Street and Cumberland Avenue met. As the Portland Jewish community suburbanized, Anshe Sfard fell on hard times. Members left to join synagogues in locations more convenient to their new homes or for other reasons. Records and Judaica were rescued by Morris Isenman and stored in his garage for forty-five years, until they were donated in 2010 to Maine Historical Society.[xxi] Four Torahs were given to Beth Israel synagogue in Old Orchard Beach and Shaarey Tphiloh, according to Isenman. Another three went to Temple Beth El and were handed on to synagogues in Jerusalem through Rabbi Harry Sky. The silver Judaica—menorah, kiddush cup—may have gone to Temple Beth El, but no records confirm that. [xxii] In any case, no one is able to identify it or the Torahs. Although the ark ornament was rescued by Isenman and is currently at MHS, the ark itself was moved to the small chapel at Mt. Carmel Cemetery. According to Arthur Cope, when the chapel was torn down in recent years there was “nothing of significance left.”[xxiii] The two yahrzeit plaques went to Etz Chaim Synagogue at 267 Congress Street and are currently hanging in the first floor chapel. Sometime in the 1960s, Anshe Sfard was abandoned and boarded up. It disappeared from the Portland Directory in 1967, and on August 5, 1983 the building was razed.[xxiv]

Besides the expected immigrant drift to suburbia, by the mid 1950s the blight of urban renewal had hit the adjacent India Street and Bayside areas hard. Whole neighborhoods were devastated¾among the first to go were Vine, Chatham and Deer Streets, below the other side of Congress Street, in 1954.[xxv] Later in the 1960s, more would go to accommodate a cross-town throughway, Franklin Arterial, and a large housing complex, Franklin Towers. On Franklin Street itself, many families in this ethnically diverse area were forced to leave as their multi-family houses were demolished. Only two or three buildings on this street were spared out of approximately one hundred.[xxvi] Upper Wilmot, upper Chapel and Quincy Streets, among others in the Bayside area of Portland, were also erased. All around Anshe Sfard, which had been abandoned sometime in the late 1950s or early 1960s, apartments and small businesses vanished leaving the boarded-up synagogue in decrepit solitude amid parked cars and whizzing traffic. Today, a parking lot and a long stretch of asphalt have taken the place of this once lively neighborhood that for a hundred years had seen homes, churches, synagogue, Chinese laundries, stables, civic organizations, schools, barber shops, coffee houses and family businesses on streets lined with elms.[xxvii] According to Ada Louise Huxtable, the aim of urban renewal to eradicate slums was synonymous with eradicating history. In the case of Portland, this was at least partly true.[xxviii]

There were a few other owners of the Anshe Sfard building after its board of directors sold the property around 1967.[xxix] The first was Pritham Singh, a Massachusetts man who became a Sikh, and whose organization claimed he wanted the building for a rehabilitation center. Portland was abuzz, especially the Jewish community, when it was revealed that Anshe Sfard was destined to become an ashram. According to Gerry Cope, there was great relief when the dreaded transformation from synagogue to ashram did not occur and the building passed to other owners.[xxx] Finally, EC Jordan Engineering purchased the building and oversaw its demolition.[xxxi] Many in the Portland Jewish community, and certainly the general public, have no idea that the congregation—or indeed the neighborhood—ever existed.

The Building

The synagogue building itself—a flat-roofed brick box with a pointed façade and concrete steps—was not very interesting. Although there were a number of stained glass windows, it has not been possible to ascertain the design and colors, assess the workmanship or identify the artisan. The interior of the synagogue was typical of the Ashkenazic style of the time, set up in the same way that Adat Israel, later known as Etz Chaim, on Congress Street, and Shaarey Tphiloh on Newbury Street, were arranged; ark in the front of sanctuary, facing southeast toward Lincoln Park, and the bimah in the middle. The second floor was a three-sided loft seating approximately one hundred women; there were 150 seats below for the men and boys.[xxxii] The kitchen was in the basement. There probably was no mikvah; if anyone needed the use of a ritual bath, the one at the rear of Shaarey Tphiloh a few blocks away was available, and later there was one at Etz Chaim up the street.[xxxiii] There was a heated vestibule that cheder Rebbe, Mr. Modes, who lived a few doors away, used for the Talmud studies that the neighborhood boys attended.[xxxiv] The interesting and unusual aspect of this synagogue, besides the aforementioned minhag and nusach of the congregation and the liturgy, was the interior design.

A photo taken on demolition day, August 5, 1983, shows amid the rubble, two wall paintings located on the north-facing interior wall of the building, the façade.[xxxv]

Although difficult to make out, one appears to be a rendering of an aqueduct, perhaps meant to evoke the one at Caesarea on the coast of Israel between Tel Aviv and Haifa. The other may be olive trees.

In his book, Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth Century Polish Community, architectural historian Thomas Hubka describes in great detail the history of Polish wooden synagogues and their fantastical paintings that often covered the interior of the synagogues from floor to the tip of the domed ceilings. The many color plates and black and white photographs comprise a wide range of illustrations taken from many sources. Common motifs are animals, including those never seen by Eastern Europeans, calligraphic painted prayers, and the signs of the zodiac. The Gwozdziec Synagogue, which is the focus of his study, has around the uppermost tier of its domed ceiling, all twelve of the symbols. [xxxvi] These can be seen in detail at www.handshouse.org.

Hubka posits several theories about the possible historic associations and antecedents of the Gwozdziec wall paintings. What meaning the Anshe Sfard paintings might have had for the artists and the Portland congregation, or what role they may have played in Jewish tradition at the time, is not clear. We can nevertheless imagine that they are connected, however tangentially, to the artistic and religious traditions of the Polish communities that Hubka describes and from which Anshe Sfard congregation members likely emigrated.

Carl Lerman, a former Anshe Sfard member, recalled that there were paintings of the zodiac symbols on the walls of the sanctuary. Although that assertion has not yet been confirmed by other interviewees, an engineer overseeing the demolition did recall a “mural.”[xxxvii] Gerry Cope describes a blue ceiling painted with clouds. Coupled with the images of the paintings in the Schechter photographs, we may conjecture that they did exist, especially with the knowledge that they were commonly used in both the Polish synagogues of the 18th century and on mosaic synagogue floors in Israel built in late antiquity, in the 4th to 6th centuries. (Their function was not strictly decorative, but served as a representation of the calendar and a framework for annual synagogue holidays and rituals.)[xxxviii]

Although it is not known if there were any animal paintings in Anshe Sfard, animals¾ real, and eschatological, such as behemoth and leviathan¾were very common among Polish synagogue wall paintings.[xxxix] Anshe Sfard did have a carved wooden nesher that sat atop the ark. The eagle is one of the creatures used to represent among other things, air, one of the four elements that are significant in Kabbalistic sources such as the Zohar. The eagle is also an important Biblical creature. Such carvings were commonly made by Ashkenazic artisans and used both religiously and commercially in items such as aronei kodesh and cigar boxes.[xl]

The American Folk Art Museum, Manhattan, in 2007, mounted an exhibit, ”Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to the Carousel,” featuring many representations of carved wooden animals, from ark ornaments to carousel horses, created by Eastern European Jewish immigrants to America between 1880 and 1920.[xli]

To the artisan who carved the Anshe Sfard eagle and to this congregation, the eagle could have been merely a type of decoration to which they were accustomed. Was the artisan local or was the carving commissioned to a New York craftsman? Were these men who devotedly pursued the study of Kabbalah? Were they knowledgeable of its enormous complexity and mysteries, or were they simply aware, as so many are today, of its most superficial symbology.

Questions

This investigation has revealed some important areas for future inquiry; there is much to discover about this synagogue and its congregants. First, it has been difficult to find information about the religious practices of this congregation. A few of the members probably were genuinely Chassidic, but no siddurim or other liturgical sources have been located. Respondents, who were very young when they last attended a service, are not able to describe the liturgy. It is agreed that there certainly were differences in the traditions from other Orthodox groups, but they were probably very small ones.[xlii]

Further, we want to know more about its founders and members over its fifty year lifespan. What Eastern European towns did they call home? A local woman reports that Anshe Sfard was referred to as the “peylisher” shul.[xliii] That at least lets us know that some members had emigrated from Poland.[xliv] Why exactly did they leave? Was it the pogroms? A wish to be with family who had previously emigrated? Why did they choose Maine? How did they make their living? Isenman describes this congregation as very poor, and that there were people who attended because there was no membership fee, as was the case then in other synagogues. He recalls that as many as 300 people attended Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services; this may have been the case because otherwise they would have had to purchase tickets to attend elsewhere.

What were the women up to? Did they maintain the home, care for the children and run small businesses, as is the case in other immigrant Jewish communities in Maine and elsewhere? There were a number of boardinghouses and corner shops in this section of Portland, types of business frequently owned and managed by women. Tax assessment photos from 1924 show many Bayside buildings being owned by women. Why and how did this ownership status occur? What role did they play in this local economy?

Why exactly was this only Portland synagogue that seems to have had long-lasting amicable relations with other congregations? There are many stories, both documented and apocryphal, of synagogue wars, stand-offs in the local butcher shop and pews being ripped from the floor. None of these involve Anshe Sfard members getting into trouble or fighting with their co-religionists in other congregations. It appears that they kept themselves to themselves from the start and any splinter groups go unnoted in available resources.

The building itself presents yet another area of investigation that is far from complete. Who designed the synagogue interior? What were the walls really like and what was their story? What did the members think about the paintings? What purpose, if any, besides aesthetic, did they serve? How did they come to be made? Who fashioned the ark?

As with so many other extinct synagogues, both nationally and in Maine, little is known. Preservation and documentation were often rudimentary at best. In fact, such tasks frequently occur under difficult circumstances, well after a congregation’s demise. There may have been interdicts regarding photographs being made in the sanctuary. Photographs of the interiors of synagogues were not de rigueur then as they are today. Where would synagogue websites and Facebook pages be without highly pixilated images of the latest window designed by a famous artist or the most recent rescue of a once beautiful and thriving Lower East Side shul? New synagogues, even in Maine, are designed and constructed for millions of dollars and photographed within an inch of their lives. Every event is recorded. But this is usually not done for historic or preservation purposes.

It is a fact that humans think and act ahistorically. Sticky photos are piled in cardboard boxes stored in basements, “junk” is tossed into the Dumpster, documents are indiscriminately selected to be hidden in genizot and forgotten, and valuable objects make their way to garage sales and are sold for pennies.

We think we invented everything. No matter in which century we live, we read or hear tales of long ago and ask ourselves why they didn’t see things then the way we do now. And so on. We know this. And we know that life moves inexorably forward. Still, it can be sad and frustrating to look back at the slow death of a congregation and its home¾dwindling membership, the vacant building, the stacks of moldy prayer books. Thirty years after the destruction of its home, it is as though this dynamic congregation of forward-looking women and men never existed. No building, no images of the building except for demolition photos taken by the local paper and an art student who happened by, very few surviving former members and even fewer stories. There is no historical marker to jog memories or to prompt investigation. Just a parking lot.

GLOSSARY

Adat Israel – Community of Israel (Jews).

Ark – Chest in which a Torah (See Torah) is housed.

Aron kodesh – Holy ark.

Aronei kodesh – Plural of aron kodesh.

Ashkenazic – Pertaining to European Jews, especially Yiddish-speaking, who settled in central and northern Europe (AHD).

Bas HaKnesses Anshe Sfard – House of Assembly of the Men of Spain (Spanish Jews).

Behemoth – A huge animal described in the Torah (AHD). Hebrew plural for “beasts.”

Bet HaMidrash HaGadol – School of Midrash (See Midrash).

Chassidic – Pertaining to a Jewish mystical movement founded in the 18th century in Eastern Europe by Baal Shem Tov (Master of the Good Name) that reacted against Talmudic learning and maintained that G-d’s presence was in all one’s surroundings and that one should serve G-d in one’s every deed and word (AHD).

Cheder – A school for Jewish children in which Hebrew and religious knowledge are taught. (OED.)

Chevra kadisha – Holy society, often a burial society.

Chevrei kadisha – Plural of chevra kadisha.

Etz Chaim – Tree of Life.

Genizot – plural of genizah, a repository where sacred Jewish artifacts are stored prior to cemetery burial.

Kabbalah – Kabbalah is a set of teachings meant to explain the relationship between an unchanging and mysterious eternal and G-d’s creation, the finite universe.

Leviathan – Monstrous sea creature described in the Torah (AHD).

Midrash – Any of a group of Jewish commentaries on the Torah compiled between 400 and 1200 CE and based on exegesis, parable and haggadic legend (AHD.)

Mikvah – Ritual bath.

Minhag – Accepted tradition or group of traditions in Judaism.

Nesher – Eagle.

Nusach – Traditional order and form of prayers.

Sephardic (Sfardic) – Pertaining to Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal during the Middle Ages until persecution culminating in the expulsion of 1492 forced them to leave (AHD).

Shaarey Tphiloh – Gates of Prayer.

Siddur – Prayer book.

Siddurim – Plural of siddur.

Talmud – A central text of Rabbinic Judaism.

Torah – Five books of Moses.

Yahrzeit – Yearly anniversary of a death (Yiddish).

Zohar – Foundational text in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah.

AHD – American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006)

OED – Oxford English Dictionary

ZODIAC SYMBOL CORRESPONDENCE WITH HEBREW MONTHS

East

Tammuz-Cancer

Av-Leo

Elul-Virgo

North

Tishri-Libra

Cheshvan-Scorpio

Kislev-Sagittarius

West

Tevet-Capricorn

Shevat-Aquarius

Adar-Pisces

South

Nisan-Aries

Iyyar-Taurus

Siva-Gemini

FOOTNOTES

[i] Simon Schama, The Story of the Jews. Written and presented by Simon Schama BBC, Thirteen Productions LLC. 2014

[ii] Ira Robinson, American Jewish Archives Journal, “Anshe Sfard: The Creation of the First Hasidic Congregations in North America,” 2005, pp. 53-66.

[iii] There were at least two other “Anshe Sfard synagogues” in Bangor.

[iv] Steven Steinbock e-mail.

[v]Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Benjamin Band, Portland Jewry: Its Growth and Development, (Portland, ME: Jewish Historical Society, 1955) p. 29.

[viii] City of Portland, Maine building permit, 1916.

[ix] Earle Shettleworth telephone conversation.

[x] Portland Directory 1920, p. 911.

[xi] Band, op cit

[xii] Rachel Miller, “Twenty Nationalities and All Americans”, Maine Memory Network. www.mainememory.net

[xiii] Young Women’s Hebrew Association minutes.

[xiv] Michael R. Cohen, Maine History, “Adapting Orthodoxy to American Life: Shaarey Tphiloh and the Development of Modern Orthodox Judaism in Portland, Maine, 1904-1976”, (Maine Historical Society) 44:2 April 2009, pp 172-195. This article provides a thoughtful and detailed description of Shaarey Tphiloh’s evolution during this period.

16 Earle Shorris. Latinos: A biography of the people NY: W.W. Norton, 1992 in Ed. Joseph Conforti. Creating Portland: History and Place in Northern New England, University of New Hampshire Press, 2005.

[xvi] Band, op cit

[xvii] Gerald Cope e-mail.

[xviii] Carol Hershelle Krinsky in Sara Ferdman Tauben, Shuln and Shulelach: Large and Small Synagogues in Montreal and Europe, Hungry I Books, 2008. Also, see http://video.forward.com/video/Montreal-s-Synagogues In “Traces of the Past: Montreal’s Early Synagogues” Sarah Ferdman Tauben documents the development of Montreal’s Jewish community from the 1880s until 1945. Much like a detective, she has pored over historic city maps and directories, sepia-coloured photos, brittle newspaper articles and long forgotten anniversary publications to track the locations of Montreal’s early synagogues. In this video interview Ferdman Tauben tells the fascinating story of Jewish immigrants in Montreal through the architectural traces of its culture. The contemporary pictures were taken by photographer David Kaufman. Read more: http://blogs.forward.com/the-arty-semite/198239/video-the-synagogue-detective-of-montreal/?#ixzz32Ai9TL54

[xix] Band, op cit.

[xx] Shaarey Tphiloh minutes, 1946.

[xxi] In 2012, the trustees of Mt. Carmel Cemetery, Gerald and Arthur Cope, and Helen Isenman donated several administrative books (pinkasim) written in Yiddish, a gilt carved eagle ark ornament and a mortgage deed dated 1917 to the Maine Historical Society. These items were saved by Helen’s husband, Morris Isenman. They were the property of the cemetery associated with Anshe Sfard and the synagogue itself.

19 Morris Isenman, oral history. Jewish Bicentennial Oral History Program, Portraits of the Past: The Jews of Portland, Konnilyn Feig, Director. Commissioned by the Jewish Federation of Southern Maine. September 1, 1977.

[xxiii] Arthur and Gerry Cope’s telephone conversation.

[xxiv] Portland Evening Express, August 5, 1983.

[xxv] Abraham J. Peck and Jean M. Peck, Images of America: Maine’s Jewish Heritage, Arcadia Publishing, 2007. This book shows a 1924 tax photo of a private residence at 36 Deer Street that was used as a shul in starting in 1883. Tax photos, 1924, of the City of Portland available on Maine Memory Network, Maine Historical Society, www.mainememory.net.

[xxvi] Scott Hanson, History of Franklin Street, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zrp5FSGjME4 These images, along with a brief overview of the history of “slum clearance” in Portland, were presented by city Historic Preservation Program Manager, Scott Hanson, at the first meeting of the Franklin Street Redesign Committee. The historic photographs shown here are from the City of Portland’s 1924 tax photo collection. As part of a tax re-evaluation in 1924, every taxable building in the city was photographed, including dozens of the historic buildings that would be destroyed to make way for the Franklin Arterial.

[xxvii] Abraham Schechter, Director of Special Collections, Portland Public Library, Portland, ME conversation.

[xxviii] Ada Louise Huxtable, New York: A Documentary Film, Ric Burns, Episode 8.

[xxix] Cumberland County Register of Deeds, Portland, ME.

[xxx] Morris Isenman, op cit., and recollection of author.

[xxxi] Alan Piecuch, EC Jordan Engineering, conversation.

[xxxii] Morris Isenman, op cit.

[xxxiii] Gerald Cope conversation.

[xxxiv] Irving Grunes conversation.

[xxxv] Abraham Schechter photo.

[xxxvi] Thomas C. Hubka, Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-Century Polish Community, Brandeis University Press, published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH. 2003.

[xxxvii] Alan Pietciuc, op cit

[xxxviii] Walter Zanger, Bible History Daily, “Jewish Worship, Pagan Symbols: Zodiac Mosaics in Ancient Synagogues”, (Biblical Archeology Society, 8-24-12)

[xxxix] Thomas Hubka, Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-Century Polish Community, Brandeis University Press, published by University Press of New England, Hanover NH, 2003.

[xl] Ibid

[xli] Martha Schwendener, New York Times,” Sacred Skills Thrive on a Merry-Go-Round”, October 5, 2007.

[xlii] Ira Robinson, op cit.

[xliii] Hazel Brenerman conversation.

[xliv] Stephen Simons, PhD, conversation.

THANK YOU TO:

Maine Humanities Council

Maine Historical Society:

Nan Cumming, Director of Institutional Advancement

Elizabeth Nash, Marketing and Events Manager

Holly Hurd-Forsyth, Registrar

William D. Barry, Research Historian

Candace Kanes, Project Scholar

Kathy Amoroso, Director of Digital Projects

Bayside Neighborhood Association

Mt. Carmel Cemetery Association

Hillary Bassett, Greater Portland Landmarks

Gerald Cope, Mt. Carmel Cemetery Association

Arthur Cope, Mt. Carmel Cemetery Association

Earle Shettleworth, Jr., Maine State Preservation Commission

Helen Isenman

Darrell Cooper, Portland Jewish Funeral Home

Dorothy “DeeDee” Schwartz, Project Evaluator

Eileen Eagan, Project Evaluator, University of Southern Maine

Stephen “Shimon” Simons

Steven Steinbock

Carl Lerman

Sara Ferdman Tauben

Abraham Peck

Steve Hirshon, Bayside Neighborhood Association

Deborah Van Hoewyk, Bayside Neighborhood Association

Abraham Schechter, Portland Public Library, Special Collections

Chris MilNeil, Portland Press Herald

Gary Nathanson

Alan Piecuch, AMEC

Herb Adams

Matt Jude Barker, Irish Heritage Center

Joel Glovsky

Louis Kornreich

Paul Giguere, State Department of Transportation

Harris Gleckman, Documenting Maine Jews

Jodi Lerman

Rabbi Harry Sky

Howard Reiche, Jr.

Stephanie Cummings

Barbara Fowler

Mark Adelson, Portland Housing Authority

Rick Knowland, City of Portland Planning Department

Having read this I thought it was very informative. I appreciate you taking the time and energy to put this short article together. I once again find myself spending a significant amount of time both reading and commenting. But so what, it was still worth it!

Pingback: Anshe Sfard: Portland’s Forgotten Chassidic Synagogue - Maine Humanities CouncilMaine Humanities Council